Planning, Flood Risk, and the Sequential Test: What Has Changed?

For clients and consultants navigating planning applications in areas at risk of flooding, there have been some key recent developments worth knowing. In this article, we consider what’s changed, what hasn’t, and what it all means for development proposals.

What is the Sequential Test?

For proposed development in an area with any level of flood risk (i.e. in flood zones 2 and 3), the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) requires the application of the sequential test. The aim of this is to steer development to areas at lowest risk of flooding from any source — whether that’s rivers, tidal water, or surface water.

If lower-risk sites are identified that are suitable for the development proposal and are reasonably available, the proposed site fails the test.

The concept of sequential tests has existed within the planning sector for a number of years and was mainly associated with proposals for retail development , since PPG6: Town Centres and Retail Developments (1996) directed that developers should look first at sites in existing town centres, then edge-of-centre, then only out-of-centre if no suitable sites were available. This was a response to the acceleration of out-of-town shopping centres in the late 1980s and early 90s.

For flooding, the first formal sequential test was introduced via PPG25: Development and Flood Risk in 2001. In this regard, the formal process has been in place for over twenty years and has been through numerous iterations in subsequent PPGs and then in the first NPPF in 2012.

A Turning Point: The Mead Case

A pivotal moment in the importance of the sequential test for flooding came with the High Court case Mead Realisations Ltd v Secretary of State and North Somerset Council [2024] EWHC 279 (Admin) in February 2024. The High Court judgement (‘the Mead Case’) established four key principles which are summarised below.

1. National Policy Takes Precedence

The Inspector determining an appeal in North Somerset had applied the national sequential test (as set out in NPPF) rather than the more restrictive local policy test contained in the Council’s Core Strategy.

The High Court upheld that approach; national policy prevails where there is inconsistency with local policy. The judge also held that the guidelines contained in the National Planning Practice Guidance (‘the PPG’) should be read as policy, and that they effectively hold the same weight as the policies in the NPPF.

2. Flexibility Is Required: A Site Should be Assessed Even If It Doesn’t Mirror Every Detail

The sequential test is not about whether a site can deliver exactly the same scheme as that proposed. Instead, it’s whether the alternative site is appropriate for the type of development proposed. A rigid, like-for-like approach undermines the purpose of the test. Developers must justify any claims that no other sites are suitable by showing why a smaller or larger or differently configured site wouldn't reasonably work.

Planning authorities and inspectors are encouraged to exercise judgment, not rigid box-ticking. A site doesn’t need to mirror every detail of the proposal to be a valid alternative.

3. Lack of a 5-Year Housing Land Supply Doesn’t Override the Sequential Test

Importantly, developers can’t argue that housing need justifies ignoring or bypassing the sequential test. Even if a council can’t demonstrate a 5-year housing land supply, and even if that engages the “tilted balance” under paragraph 11(d) of the NPPF, the flood risk policies in footnote 7 still apply — and may disapply that tilted balance if there’s a “clear reason’ for refusal, like failure of the sequential test. This reinforces that safety from flooding is a threshold issue, not one to be weighed after the fact. As an aside, it is worth noting that the term “clear reason” has now been replaced with the term “strong reason” in the revised NPPF; this may appear as a minor change, but there are of course subtle differences between the meaning of the words in this context.

4. Mitigation Cannot be Used to Bypass the Sequential Test

The judgement in the Mead Case also stated that the use of mitigation measures, such as raising ground levels so a site technically sits above predicted flood depths, do not mean that the sequential test does not need to be undertaken. That test must be applied based on existing risk, not post-mitigation conditions.

Therefore, if a site is in Flood Zone 3 or at risk from surface water flooding, the sequential test must be done first, regardless of whether one can engineer one’s way out of the risk. This ensures that development is directed away from high-risk areas where possible, not just made safer on the application site.

Applying The Mead Case: The Yatton Appeal Decision

In March 2025, the Planning Inspectorate allowed an appeal for a major housing development in Yatton, North Somerset (APP/D0121/W/24/3343144). While the site was in Flood Zone 3a, the developer had undertaken a comprehensive sequential test, and the Inspector concluded it had been passed. What’s more interesting is how the Mead Case was applied:

- The Inspector gave greater weight to the national test than to the specific North Somerset Policy, consistent with the Mead Case.

- The Inspector found that the “type of development” didn’t need to precisely match every detail of the proposal. For instance, providing 50% affordable housing wasn’t necessary for alternative sites to be considered appropriate.

- The Inspector also rejected a rigid interpretation of alternative site suitability, again following the Mead Case’s emphasis on a practical, common-sense approach.

The Faversham Appeal Decision: What If the Sequential Test Isn't Carried Out?

In contrast, the appeal for a large housing scheme in Faversham, Kent (APP/V2255/W/24/3350524), was also allowed — but not before the Inspector highlighted clear procedural failures (consistent with the Mead Case):

- The developer had not undertaken the sequential test.

- Raising ground levels to mitigate flood risk didn’t excuse the absence of the sequential test.

- The Inspector was highly critical of this omission and stated that it conflicted with the NPPF, which makes it clear that land raising does not exempt proposals from needing to apply the sequential test (see para 175 of the NPPF).

Yet, in the end, the development was allowed because the risk was very limited in practice, and mitigation could make the site safe. The Faversham appeal decision underlines that while failure to apply the sequential test is a policy breach, Inspectors can still consider the real-world implications in the planning balance.

What the Latest NPPF Says

The revised NPPF (December 2024) reinforces these principles, and remains the primary guidance for undertaking the sequential site assessment for flood risk:

- Paragraph 170: Reaffirms the aim to steer development away from flood risk and defines the need for a sequential test.

- Paragraph 175: Clearly states land raising cannot be used to avoid the need for the sequential test.

- PPG (Para 028): Defines “reasonably available” sites broadly and includes those not in the applicant’s ownership.

Summary and Conclusions

The sequential test has become a more pertinent and prominent consideration for planning applications over the past 18 months and requires careful consideration and strategic advice at the masterplan stage of a project. Moreover, the sequential test also has potential implications for the identification of ‘grey belt’ sites, as the definition in the NPPF states that ‘grey belt’ excludes land where footnote 7 would provide a “strong reason for refusing or restricting development”.

This consideration is evidenced is in an appeal decision issued by the Planning Inspectorate earlier today (5th August 2025) for a ‘grey belt’ site in Hemel Hempstead, which has allowed a residential-led scheme on Green Belt land. The appeal decision (ref: APP/A1910/W/24/3345435) deals with the matter of flood risk within the site and concludes that this did not add up to a “strong reason” for refusal. In other words, the outcome of the flood risk sequential test was not determinative.

In the decision, the Inspector affirmed that the sequential test, as required by the NPPF, aims to direct development to areas with the lowest risk of flooding. However, the decision emphasised that the test must be applied with realism and flexibility, particularly in areas facing severe housing shortfalls. Referencing the Mead Case, the Inspector accepted that even if limited alternative sites in lower flood zones existed, their capacity (32 dwellings) was negligible compared to the borough’s substantial shortfall (over 6,500 homes). Therefore, in such contexts, less sequentially preferable sites can still be justified if they help meet pressing housing needs.

The Inspector concluded that the appeal site, while partially at risk of flooding, could be rendered safe through effective mitigation measures, and that no sequentially preferable, reasonably available sites had been identified. Importantly, the sequential test was not treated as determinative: any residual risk was instead considered within the broader planning balance. Ultimately, the appeal demonstrated that in cases of acute housing need, the rigid application of the sequential test may be relaxed, provided that flood risks are properly addressed and the development aligns with wider sustainability and policy objectives.

Contact Us

Union4 Planning regularly inputs to and co-ordinates sequential tests alongside professional flood risk consultants. For specific advice on sequential tests or navigating flood-related planning issues, please get in touch. We have learned from working closely with flooding experts that it is prudent to ensure such constraints are fully considered in the preparation of planning applications – the earlier the better.

Email planning@union4.co.uk

Other news

See all

London Housebuilding: Emergency Measures

The Government and GLA are currently consulting on two documents aimed at stimulating and reviving housing delivery across London, in response to a…...

Read now

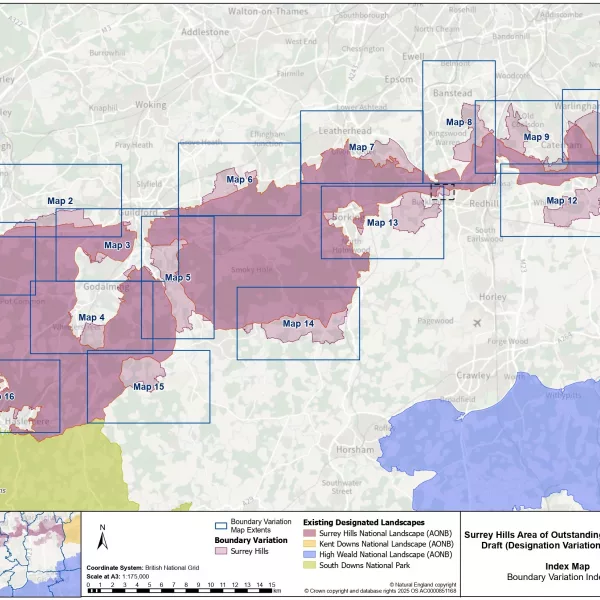

Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty - Boundary Extensions: Last opportunity to make representations

Natural England have given notice of their intention to Vary the Designation Order to include boundary extensions to the Surrey Hills Area of…...

Read now